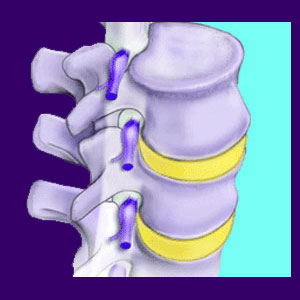

Foraminal stenosis is a spinal condition which is defined as a reduction in the size of the one or more of the neuroforaminal spaces. A significant decrease in size of these openings may affect one or more spinal nerve roots, possibly enacting painful symptoms.

The foramen are the openings between vertebrae which allow the nerve roots to exit from the spinal column. There are foramen between each vertebrae allowing the various nerves to branch off from the spinal cord and serve the regional neurological requirements of the body. Stenosis is a condition which describes a narrowing or closing of a typical anatomical space. Therefore, stenosis of the neuroforamen is the condition in which one or more foramen narrow, possibly impinging on a nerve root. This condition is commonly cited as the cause of a pinched nerve.

This dialog examines neuroforaminal narrowing and provides an objective view of this controversial condition to help diagnosed patients to better comprehend the meaning of stenotic foraminal openings.

Foraminal Stenosis Causes

This type of stenosis can be caused by a great number of possible reasons, many of which are normal to experience as we get older:

Herniated discs can bulge into the foraminal canal, constricting the nerve signal and possibly inducing symptoms.

Enlargement of a particular part of the vertebrae called the uncinate process can cause narrowed cervical foramen. The uncinate processes are projections on the sides of certain cervical vertebrae.

Spinal arthritis can cause degeneration of the foraminal openings. Osteophytes can also build up around the foramen, possibly compressing a spinal nerve root.

Abnormal spinal curvatures, such as hyperlordosis, hyperkyphosis or scoliosis, can all create narrowed foramen when the curvatures are severe.

Vertebral misalignments, such as retrolisthesis and anterolisthesis, can cause the foramen to suffer a significant reduction in size and may easily trap nerves in unlucky patients.

Foraminal Stenosis Symptoms

Being that foraminal narrowing is not symptomatic in itself, there is usually no pain directly caused by stenosis of the foraminal openings. Pain and other neurological symptoms are only present if the narrowed foramen actually compresses a nerve. In this case, the symptoms are exactly identical to any other pinched nerve condition.

The most common physical symptoms include pain, tingling, numbness and weakness experienced locally and in the area served by the affected nerve.

This condition is also a possible cause of chronic sciatica in certain patients.

Stenosis of the Neural Foramen

Neuroforaminal narrowing can be a problem for a small minority of patients with specific anatomical conditions. Most diagnosed cases of stenosis of the foramen are simply vilifying the condition as yet another scapegoat on which to blame back pain. Unlike many other unfairly demonized conditions, chronic symptoms are certainly possible from the development of severe foraminal narrowing. This makes the distinction between true physical cases of stenosis of the foramen and scapegoat versions even harder to differentiate than usual.

However, lasting pain is not likely even if a nerve is definitively compressed. Clinical research states that ongoing nerve compression causes objective weakness and numbness in the anatomical region served by the nerve. These symptoms will be verifiable by nerve conduction testing. Therefore, patients with chronic pain do not fit the typical profile of a true pinched nerve diagnosis, regardless of the severity of the foraminal stenosis change. In these instances, there are several possible explanations:

First, another structural spinal condition may be sourcing the symptoms with the stenosis acting as a scapegoat. Second, the nerve may be affected partially, but not truly compressed. This is a speculative theory, since many doctors do not feel that mass effect, without compression, or nerve displacement are enough to cause these types of symptoms. Finally, there may be some nonstructural processes, such as disease, infection or ischemia causing the pain.

Consult with your neurologist to ensure the most accurate diagnostic evaluation possible.