Neuroforaminal narrowing is a technical term referring to a decrease in the size of specific anatomical openings that are used as nerve root exit points from the spinal column. In the back and neck pain sector, this condition is also called narrowing of the neuroforaminal spaces or foraminal stenosis. Many laymen call the condition a pinched nerve, although this is a misconception. Most foraminal stenosis conditions do not affect the nerve passing through the size-decreased passageway. Only a small minority of patients with extreme foraminal patency loss will suffer a true compressive neuropathy.

This informative essay defines neuroforaminal narrowing, as well as examines the causes of this normal and expected part of the spinal aging process.

What is Neuroforaminal Narrowing?

Nerve roots branch off the spinal cord at every vertebral level in order to form the complex network of neurological tissues that innervate the entire human anatomy.

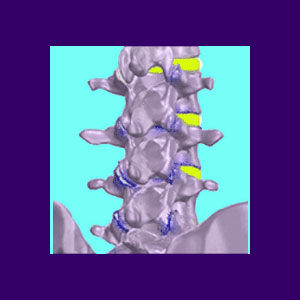

The neuroforamen are the openings between each vertebral bone that allow the nerve roots to exit the spinal column to the left and right sides. Typically, these foraminal spaces are much larger than they need to be, in order for the nerve to pass safely through without impediment. However, these openings can be narrowed through various bodily processes.

When the neuroforamen are said have lost patency, this means that the sides of the space are closing in on the nerve root, possibly effacing the nerve structure or even compressing the nerve in rare instances. It must be noted that the vast majority of cases of narrowed foramen are not symptomatic and will not cause any pain or related neurological effects, since the nerve still has more than enough room to exit the spine without constriction.

In our experience, the diagnosis of a pinched nerve, based on visualized foraminal stenosis, is one of the most subjective of all back or neck pain explanations. Pinched nerve diagnoses also suffer from a general lack of logic in many cases, since the symptoms do not match the clinical expectations for location or expression. Unfortunately, many pinched nerve diagnoses are made speculatively and without the benefit of clinical symptom correlation that should be provided by an expert in spinal neurology.

Causes of Foraminal Narrowing

There are many possible reasons why the neuroforaminal spaces may decrease in size, including any or all of the following contributors:

Herniated discs are the most common cause of transitory foraminal stenosis, since many varieties of disc abnormalities can block the foraminal openings and possibly affect the exiting nerve root. Paramedial herniations might partially efface the foraminal space, while foraminal herniations can bulge directly into the opening. In rare scenarios, extraforaminal herniations, also called far lateral herniations, can affect nerve tissues after they already exit the foraminal space, making diagnosis a far more convoluted endeavor.

Degenerative disc disease is a virtually universal source of foraminal shrinkage in the lower lumbar and mid to lower cervical spinal regions. Disc desiccation brings the spinal vertebrae closer together, minimizing available space within the foramen. Disc degeneration also facilitates and exacerbates the arthritic processes in the backbone.

Osteoarthritis in the spine will cause bone spur formations which will narrow the neuroforaminal spaces. These changes are commonplace in the cervical and lumbar spinal regions and are considered typical aspects of spinal aging.

Spondylolisthesis, and other vertebral misalignment issues, may certainly narrow the foraminal spaces at affected levels, when the 2 sides of the bones that form the openings no longer align properly.

Scoliosis, and other spinal curvatures, such as atypical lordosis and kyphosis, may decrease the patency of the nerve foramen at affected levels.

Vertebral fractures can compromise the neuroforamen with bone fragments or debris. Compression fractures in the elderly are a common source of foraminal stenosis, as well as central spinal stenosis.

Some patients simply demonstrate less patent foraminal spaces for idiopathic reasons. Many of these conditions might be congenital, while others may be related to developmental issues that can not be traced to a definitive source explanation.

Neuroforaminal Narrowing Conclusion

Remember that the foraminal openings are far larger than they need to be for the nerve to pass through unimpeded. Even moderate to advanced foraminal space narrowing is not guaranteed to enact pain in most cases. In order for symptoms to be virtually assured, the foramen would have to be almost completely closed off, definitively pinching the affected nerve root.

Even in these extreme circumstances, chronic back or neck pain are rarely the lasting results. A real pinched nerve may be acutely painful for a time, but will typically give way to objective numbness and regional weakness, rather than enduring discomfort. In these cases of true neurological constriction, there are many possible treatment regimens that might prove to be effective, including nonsurgical spinal decompression and various types of surgical intervention.